After 4 years of blogging, 82 blog posts (including this one), countless writers and contributors, an ever-changing, fun, and knowledgeable blog editorial group, aka the Blog Bunch / Blog Group, we have come to the end of the road. This will be our final blog post, and we have invited current and past blog group members to share their highlights from the blog.

In addition to the group members who have contributed their highlights below, the current blog group would like to thank the following: Ana Shah Hosseani, Christopher Hart, Emily Pyers, Emma Chapman, Emma Nelms, Jasmine Castellano, Lyn Torres, Miranda Francis, and Sarah McQuillen (Photo by opera infinita on Unsplash).

To our valued readers, we have enjoyed and appreciated your support from the very beginning. Thanks for reading and enjoy this last post 🙂

Danielle Degiorgio, Digital & Information Literacy Adviser, Edith Cowan University (previous blog group member):

Working with the Digital Dexterity blog editorial team, or, as we liked to call ourselves, the ‘Blog Bunch’, was an awesome experience, full of laughter and unforgettable moments. Our Teams’ chat was constantly filled with random GIFs that often wouldn’t load and multiple mentions of ‘scosk’ which took on a life of its own with Ruth even writing a mock post about it that I wish we published.

Thanks to the support and knowledge-sharing of this amazing, talented group of librarians – Simone, Kristy, Emma, Sarah, Marianne, Krista, to name a few – I not only improved my editorial skills but also discovered new ways of thinking about digital learning and engagement. It was truly fun to be a part of such an incredible team, and I’ll always be grateful for the friendships I’ve made within the Digital Dexterity community of practice. A special shout-out to Sara, who was the heart of the ‘Blog Bunch’ and the CoP. Sara, your hard work and organisation kept us all on track and without you we’d have been too distracted to get anything done! Thank you all.

Emeka Anele, Learning Designer, Deakin University:

As I look back to the beginning of my time with the DigiDex Group, I am overwhelmed by the incredible experiences and growth I’ve witnessed. I was invited by a colleague to attend a meeting, and I just never left. Joining the DigiDex blog group felt like rolling down a hill of digital literacy, only to be warmly welcomed at the bottom. This group picked me up and made me feel part of something special.

One of the greatest highlights of my time with the DigiDex blog group has been the chance to collaborate with passionate colleagues from different libraries. Everyone approaches the work with such enthusiasm and optimism. This has been an asset to the editorial group as we enter a catch-up with no idea about the next blog post and leave with ten new ideas.

I’ll always be immensely grateful for the guidance and support I received from other members of the editorial group. The joy and optimism I experienced has left a lasting impact on me. Though this is the end of the blog, the future looks bright. I am confident that our paths will cross again soon, to continue shining a light on digital literacy work in libraries.

Kasthuri Anandasivam, Digital Curriculum Librarian, University of South Australia:

In my short time as a member of the CAUL DigiDex blog group, I have been amazed by how much I have learned and the inspiring people I have met from the different institutions. The group has been a safe, supportive space where I can ask questions—no matter how basic and know I will not be judged. I have gained insights into many new tools used by different institutions in higher education. Contributing to a post on an emerging and timely topic was incredibly rewarding. I have also been able to share what I have learned with my colleagues, sparking new ideas and conversations within my own institution. It has been a privilege to be part of such a creative, generous, and forward-thinking community.

Kristy Newton, Digital Literacies Coordinator, University of Wollongong (previous blog group member):

I was lucky enough to be a member of the CAUL Digital Dexterity blog team for a number of years and really enjoyed my time as a member. The team is an amazing, hard working group of folks with a genuine passion for digital dexterity. During the tumultuous times of 2020-2022 opportunities for in person collaborations were very limited but the virtual nature of the team made it possible to continue working together and producing a blog we were really proud of. The team kept an actively running chat in the background of our MS Teams site that covered everything from blog tasks and questions about meetings or post details to personal insights, advice, laughs, GIF preferences, and extremes in weather in our respective locations. As the pandemic eased, the blog continued and so did the group chat.

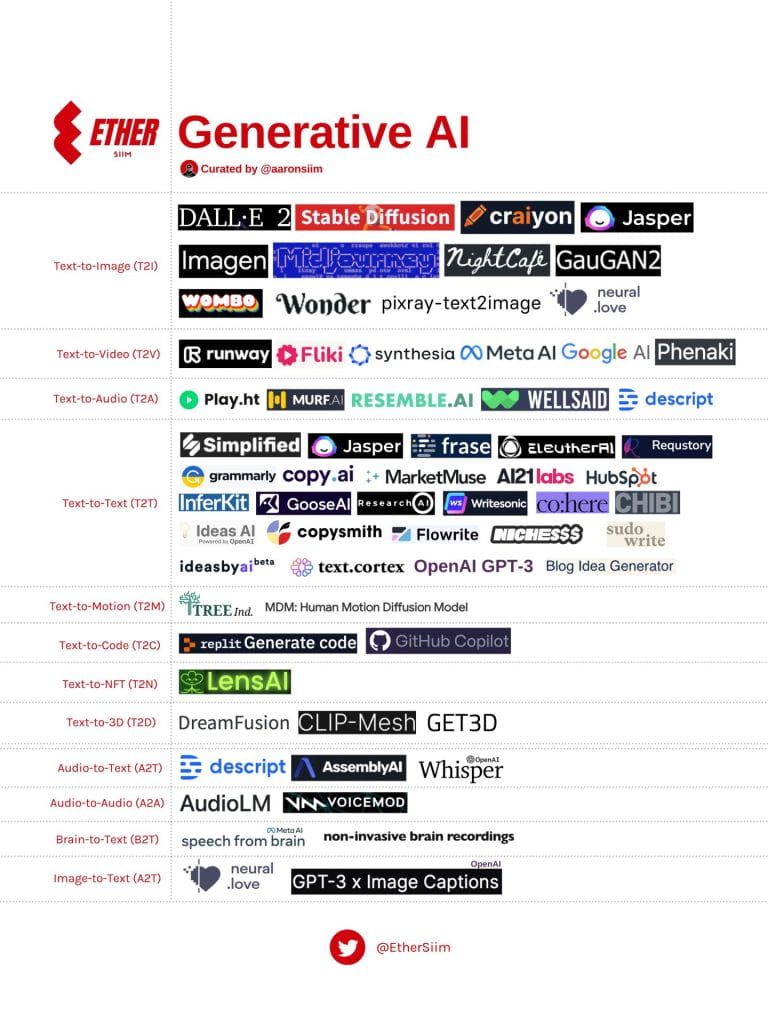

We witnessed the rise and rise of generative AI and its impact on higher education and libraries and tried our best to cover it in blog form. We dipped our toes into SEO optimisation and the intricacies of the Edublogs platform that hosted the blog. We made lots of great connections with blog post authors and evolved our collaborative approaches as the blog group membership shifted over time. It’s been a fantastic project to be part of and I think everyone involved should be very proud of the contributions we have made to the discourse around digital dexterity in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand.

Krista Yuen, Teaching and Learning Librarian, University of Waikato | Te Whare Wānanga o Waikato:

I joined the DigiDex blog group around the beginning of what we could probably call the GenAI and ChatGPT trend, and it was an exciting time to be involved in a blog that explored and discussed ideas around digital literacy. We had some very enthusiastic Zoom meetings, which I always left feeling very inspired and full of new ideas to explore. This group, from the get-go, has been very warm and welcoming and our meetings have often been a highlight of my month.

It has been great meeting and working with lots of dedicated librarians from across the Tasman, while also facilitating discussions, sharing ideas, and learning from each other about everything digital dexterity, especially in the world of tertiary libraries. It’s been a wild ride, and I am looking forward to our paths crossing again.

Marianne Sato, Digital Learning Specialist, University of Queensland (previous blog group member):

I really enjoyed my time working with the Digital Dexterity Blog Group. Getting to know the other blog group members was a highlight for me, and hearing about all the interesting work they were doing at their own institutions.

I continued to enjoy reading the blog and learning new things that I could apply to my work even after I was no longer a member of the group.

Ruth Cameron, Open Education and Digital Learning Advisor, University of Newcastle (previous blog group member):

Being part of the DigiDex blog group has been one of my life’s highlights! The group has been so creative, generous, and innovative. We learned how to use Edublogs, schedule posts, analyse usage statistics, and other fun things like complying with all the different permissions for reposting. We learned how to write engaging blog posts that could educate readers about different digital dexterities. And we did all this in addition to our ‘normal’ work as librarians. It was a real wrench when I had to leave the group, and I’m grateful for the chance to have been part of such a wonderful project.

Sara Davidsson, Member Services & Governance Lead, CAVAL:

Starting a blog from scratch with colleagues from across Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic was…extremely rewarding and fun! We started in association with our Championing the Digital Dexterity Framework Virtual Festival and have since covered topics such as: advocating for OERs, digital identity, and copyright. Virtual collaboration, building connections, and fostering flexibility have all been integral parts of keeping the blog running and the content fresh.

In addition to the cross-Tasman Sea collaboration, the connection we made with Mish Boutet (Digital Literacy Librarian at the University of Ottawa in Canada) was a blog highlight for me. Mish joined the Digital Dexterity Champions as a guest and introduced us to Ateliers sur demande | Instant Workshops through both his blog post and presentations. The opportunity to learn from others through the blog in this way has been inspiring!

Simone Tyrell, Learning Designer, Deakin University (previous blog group member):

When we first started the Digital Dexterity Blog, I think it’s fair to say not only did we not know each other but for most of us we’d never run a blog or been a part of a blog editorial team before. We came together as a group of librarians, passionate about digital literacy and lifelong learning. We had a clean slate to start the blog as we wished, we had lots of ideas and between us a variety of skills and knowledge. Whilst running the blog was a learning curve, choosing the platform, scheduling posts, learning about subscriptions, editing posts, and more, what I remember most from my time with the group is the editorial team itself (aka the blog group).

From the beginning of the blog, the blog group proved to be a safe and welcoming space, a group of people whose skills complemented each other, who collaborated seamlessly to get things done, and, most importantly, who supported each other. I always looked forward to our meetings, we always got work done but we also took the time to breathe and take some space. The blog group is what I missed the most when I changed roles and had to hand the baton over (don’t worry I kept reading the blog).

So, to my fellow blog groupers, as a former group member and reader, thank you for all your hard work and collegiality. To all our contributing authors and of course our readers, we couldn’t have done it without you, thank you.

Thanks for having me and bye just for now!