by Rachel Cunneen, Senior Lecturer in English and Literacy Education, Student Success and LANTITE coordinator, University of Canberra and Mathieu O’Neil, Associate Professor of Communication, News and Media Research Centre, University of Canberra

Disclaimer: This post was originally published in The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence and is used with the authors’ permission.

At the start of each university year, we ask first-year students a question: how many have been told by their secondary teachers not to use Wikipedia? Without fail, nearly every hand shoots up. Wikipedia offers free and reliable information instantly. So why do teachers almost universally distrust it?

Wikipedia has community-enforced policies on neutrality, reliability and notability. This means all information “must be presented accurately and without bias”; sources must come from a third party; and a Wikipedia article is notable and should be created if there has been “third-party coverage of the topic in reliable sources”.

Wikipedia is free, non-profit, and has been operating for over two decades, making it an internet success story. At a time when it’s increasingly difficult to separate truth from falsehood, Wikipedia is an accessible tool for fact-checking and fighting misinformation.

Why is Wikipedia so reliable?

Many teachers point out that anyone can edit a Wikipedia page, not just experts on the subject. But this doesn’t make Wikipedia’s information unreliable. It’s virtually impossible, for instance, for conspiracies to remain published on Wikipedia.

For popular articles, Wikipedia’s online community of volunteers, administrators and bots ensure edits are based on reliable citations. Popular articles are reviewed thousands of times. Some media experts, such as Amy Bruckman, a professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology’s computing centre, argue that because of this painstaking process, a highly-edited article on Wikipedia might be the most reliable source of information ever created.

Traditional academic articles – the most common source of scientific evidence – are typically only peer-reviewed by up to three people and then never edited again.

Less frequently edited articles on Wikipedia might be less reliable than popular ones. But it’s easy to find out how an article has been created and modified on Wikipedia. All modifications to an article are archived in its “history” page. Disputes between editors about the article’s content are documented in its “talk” page.

To use Wikipedia effectively, school students need to be taught to find and analyse these pages of an article, so they can quickly assess the article’s reliability.

Is information on Wikipedia too shallow?

Many teachers also argue the information on Wikipedia is too basic, particularly for tertiary students. This argument supposes all fact-checking must involve deep engagement. But this is not best practice for conducting initial investigation into a subject online. Deep research needs to come later, once the validity of the source has been established.

Still, some teachers are horrified by the idea students need to be taught to assess information quickly and superficially. If you look up the general capabilities in the Australian Curriculum, you will find “critical and creative thinking” encourages deep, broad reflection. Educators who conflate “critical” and “media” literacy may be inclined to believe analysis of online material must be slow and thorough.

Yet the reality is we live in an “attention economy” where everyone and everything on the internet is vying for our attention. Our time is precious, so engaging deeply with spurious online content, and potentially falling down misinformation rabbit holes, wastes a most valuable commodity – our attention.

Wikipedia can be a tool for better media literacy

Research suggests Australian children are not getting sufficient instruction in spotting fake news. Only one in five young Australians in 2020 reported having a lesson during the past year that helped them decide whether news stories could be trusted.

Our students clearly need more media literacy education, and Wikipedia can be a good media literacy instrument. One way is to use it is with “lateral reading”. This means when faced with an unfamiliar online claim, students should leave the web page they’re on and open a new browser tab. They can then investigate what trusted sources say about the claim.

Wikipedia is the perfect classroom resource for this purpose, even for primary-aged students. When first encountering unfamiliar information, students can be encouraged to go to the relevant Wikipedia page to check reliability. If the unknown information isn’t verifiable, they can discard it and move on.

More experienced fact-checkers can also beeline to the authoritative references at the bottom of each Wikipedia article.

In the future, we hope first-year university students enter our classrooms already understanding the value of Wikipedia. This will mean a widespread cultural shift has taken place in Australian primary and secondary schools. In a time of climate change and pandemics, everyone needs to be able to separate fact from fiction. Wikipedia can be part of the remedy.

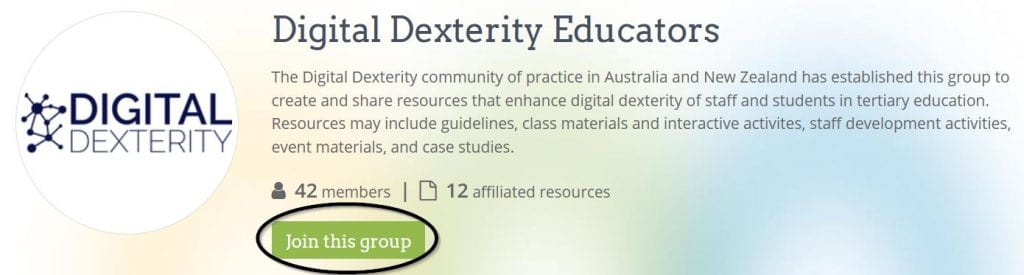

Would you like to contribute to our blog?

If you have ideas, or if you would like to contribute posts directly, drop us a line at DigitalDexterityBlog@caval.edu.au.