By Kristy Newton, Digital Literacies Coordinator (UOW Library)

Digital literacies, digital capabilities, digital dexterity… no matter what you call them, these are an essential and complex set of practical skills, attitudes and contextual understanding that help us navigate and interact with the digital world. They can span everything from learning how to use a new piece of software, to understanding how communication styles differ depending on the channel you are using to communicate, to developing a growth mindset that enables you to engage in a process of continual learning and development. This post outlines the process of developing the UOW Student Digital Skills Hub as a strategy for supporting student digital skill development.

A collaborative approach

At UOW, we recognised that a collaborative approach was essential for supporting student digital literacies and that this collaboration needed to be seamless for students to access. There had been collaborative work on developing an institutional approach to digital literacies for a few years, but the unexpected challenges of COVID19 and the rapid transition to remote learning meant that a lot of that work was paused to allow staff to address the immediate challenges presented by the pandemic. Libraries are often champions of digital literacy development, but the complex interplay of practical skills and digital behaviours means that digital literacy support at an institutional level spans several units with areas of expertise. The IT support units are an obvious match for the development of technical skills, but the development of digital capabilities at University also incorporates clever learning design that means students encounter these development opportunities in ways that are meaningful for their learning, and a future careers perspective that contextualises their skill development in relation to their professional post-University lives.

Stakeholders from the Pro Vice Chancellor (Students) Unit, Information Management and Technology Services (IMTS) Unit, and Learning Teaching & Curriculum (LTC) Unit are all strategic partners in the creation of the Digital Skills Hub. While the Library has a strong history of supporting digital literacies, as well as supporting the more traditional information literacies, it was important to us, that the site was not recognised solely as a Library site. We felt that this might compromise the value of the site for students who might think it was just about using databases rather than the broader range of digital skills and behaviours that make up their everyday lives.

The Digital Skills Hub

In late 2021, the Deputy Vice Chancellor (Academic and Student Life) revitalised the institutional conversation about digital literacies as part of a strategy for supporting student success, and identified the Library as a key stakeholder in this initiative. In response, we created an online Digital Skills Hub – a one-stop shop for students to be able to access all the digital literacy support that they needed. The Hub provides a consistent location for students who don’t know where to find digital literacy support, recognising that they often need to seek support from a variety of different units and departments, but don’t know which unit to approach for help with their specific problem. Having all the content in one place makes this an easier proposition, particularly for students who are less digitally literate. Pragmatically, because we had the support of the DVC (A&SL), we were able to secure support in embedding a link to the Digital Skills Hub in all the subject Moodle sites. This means that it was easily accessible for most students, in a location that they were already accessing for academic purposes.

One of the factors that made the Digital Skills Hub possible, was the acquisition of the JISC Digital Capabilities service. This included the Discovery Tool, a tool which allows students to undertake a self-assessment and receive a personalised report on their digital skills. Alongside the Discovery Tool, the JISC site provided a suite of support resources, and capacity for us to create UOW specific support resources that are embedded in the JISC reports. The JISC interface also provides us with valuable information in the form of an institutional dashboard. This highlights student skills across the different capability areas and provides a heat map of where the strengths and areas for development lie across different student types and different faculties. The data is de-identified, so we can’t see what a particular students progress might look like, but it does give us a good idea of trends, enabling us to target support services where they are needed.

A one stop shop for digital skills information

There are three main ways that the Digital Skills Hub supports students:

– It provides them with access to the JISC Discovery Tool, a self evaluation tool that illustrates each student’s personal strengths and weaknesses in relation to digital skills and provides them with a customised report and suggested actions/resources for developing those skills further.

– It explores Digital Capabilities through the lens of the JISC Digital Capabilities Framework, and highlights how those framework areas relate to everyday skills and digital behaviours

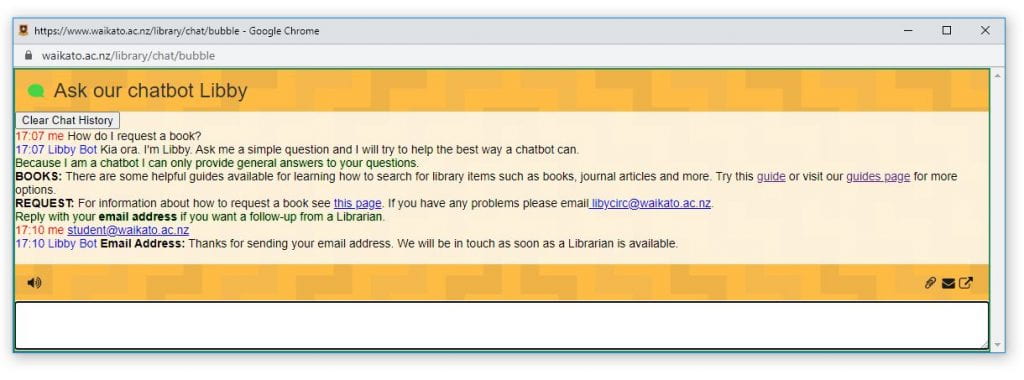

– It provides them with easy access to a knowledge base of FAQs on a variety of digital skills topics and gives them the opportunity to chat/ask a question. This knowledge base incorporates existing relevant FAQs as well as newly created FAQs that are specifically designed to support the needs of the Hub.

There is also a rating system for students to rate their satisfaction with the site, as well as a link for them to provide feedback.

Key points to consider

For institutions interested in doing something similar, the following points are worthy of consideration.

- It’s important to get the strategic support of the different units that make up the digital literacies support services for students. Creating a site where some support is offered, but students need to go elsewhere for different kinds of tasks, just creates barriers for students.

- An accessible and well-designed platform is key to the success of the site. You want to make sure that students with lower levels of digital skills can access the site and find it easy to navigate.

- Centre the development of the site on the needs of the students who will be using it. We are using an iterative design process, which means that we take on board student feedback and insights from the literature to inform the way the site develops. We see the Digital Skills Hub as a constantly evolving resource that will continue to be shaped and developed by the needs of the people using it.

Six months on from the creation of the site, we are currently engaged in a process of seeking feedback to inform the way that the site develops in the future. This is driven by an iterative, human-centred approach to content development that commits to continuously evaluating whether the site meets user needs, and adapting and evolving the site to ensure it continues to do so.