Over the break we read and loved this article from The Conversation, originally published on 18 December 2023. We hope you do too!

T.J. Thomson, RMIT University and Daniel Angus, Queensland University of Technology

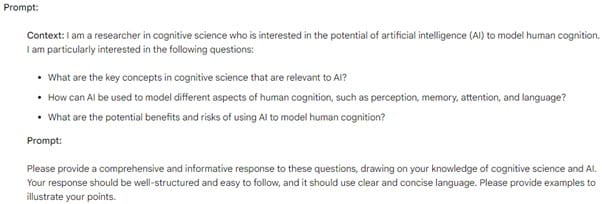

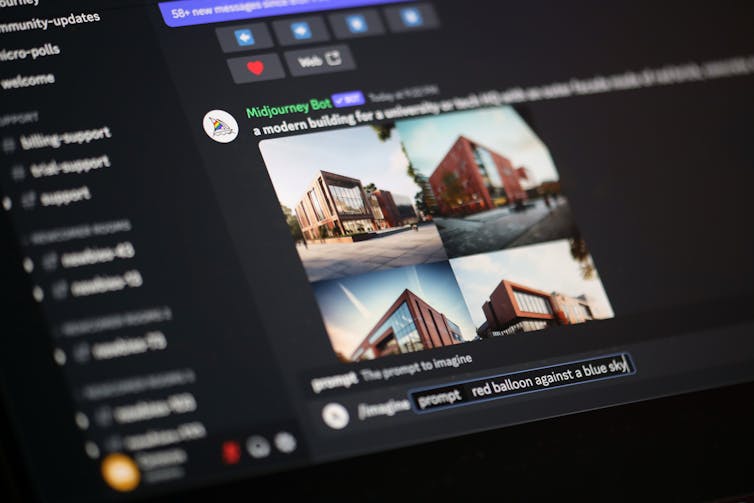

Imagine this. You need an image of a balloon for a work presentation and turn to a text-to-image generator, like Midjourney or DALL-E, to create a suitable image.

You enter the prompt: “red balloon against a blue sky” but the generator returns an image of an egg instead. You try again but this time, the generator shows an image of a watermelon.

What’s going on?

The generator you’re using may have been “poisoned”.

What is ‘data poisoning’?

Text-to-image generators work by being trained on large datasets that include millions or billions of images. Some generators, like those offered by Adobe or Getty, are only trained with images the generator’s maker owns or has a licence to use.

But other generators have been trained by indiscriminately scraping online images, many of which may be under copyright. This has led to a slew of copyright infringement cases where artists have accused big tech companies of stealing and profiting from their work.

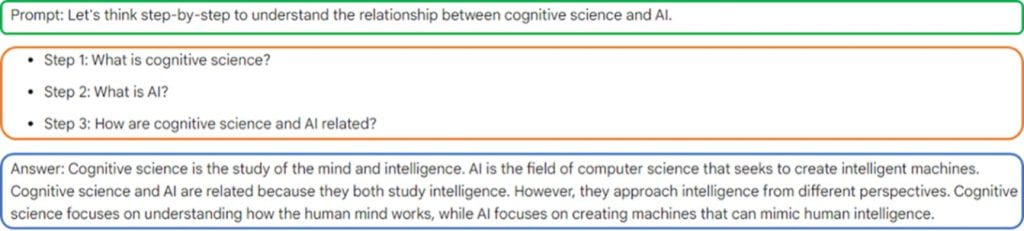

This is also where the idea of “poison” comes in. Researchers who want to empower individual artists have recently created a tool named “Nightshade” to fight back against unauthorised image scraping.

The tool works by subtly altering an image’s pixels in a way that wreaks havoc to computer vision but leaves the image unaltered to a human’s eyes.

If an organisation then scrapes one of these images to train a future AI model, its data pool becomes “poisoned”. This can result in the algorithm mistakenly learning to classify an image as something a human would visually know to be untrue. As a result, the generator can start returning unpredictable and unintended results.

Symptoms of poisoning

As in our earlier example, a balloon might become an egg. A request for an image in the style of Monet might instead return an image in the style of Picasso.

Some of the issues with earlier AI models, such as trouble accurately rendering hands, for example, could return. The models could also introduce other odd and illogical features to images – think six-legged dogs or deformed couches.

The higher the number of “poisoned” images in the training data, the greater the disruption. Because of how generative AI works, the damage from “poisoned” images also affects related prompt keywords.

For example, if a “poisoned” image of a Ferrari is used in training data, prompt results for other car brands and for other related terms, such as vehicle and automobile, can also be affected.

Nightshade’s developer hopes the tool will make big tech companies more respectful of copyright, but it’s also possible users could abuse the tool and intentionally upload “poisoned” images to generators to try and disrupt their services.

Is there an antidote?

In response, stakeholders have proposed a range of technological and human solutions. The most obvious is paying greater attention to where input data are coming from and how they can be used. Doing so would result in less indiscriminate data harvesting.

This approach does challenge a common belief among computer scientists: that data found online can be used for any purpose they see fit.

Other technological fixes also include the use of “ensemble modeling” where different models are trained on many different subsets of data and compared to locate specific outliers. This approach can be used not only for training but also to detect and discard suspected “poisoned” images.

Audits are another option. One audit approach involves developing a “test battery” – a small, highly curated, and well-labelled dataset – using “hold-out” data that are never used for training. This dataset can then be used to examine the model’s accuracy.

Strategies against technology

So-called “adversarial approaches” (those that degrade, deny, deceive, or manipulate AI systems), including data poisoning, are nothing new. They have also historically included using make-up and costumes to circumvent facial recognition systems.

Human rights activists, for example, have been concerned for some time about the indiscriminate use of machine vision in wider society. This concern is particularly acute concerning facial recognition.

Systems like Clearview AI, which hosts a massive searchable database of faces scraped from the internet, are used by law enforcement and government agencies worldwide. In 2021, Australia’s government determined Clearview AI breached the privacy of Australians.

In response to facial recognition systems being used to profile specific individuals, including legitimate protesters, artists devised adversarial make-up patterns of jagged lines and asymmetric curves that prevent surveillance systems from accurately identifying them.

There is a clear connection between these cases and the issue of data poisoning, as both relate to larger questions around technological governance.

Many technology vendors will consider data poisoning a pesky issue to be fixed with technological solutions. However, it may be better to see data poisoning as an innovative solution to an intrusion on the fundamental moral rights of artists and users.

T.J. Thomson, Senior Lecturer in Visual Communication & Digital Media, RMIT University and Daniel Angus, Professor of Digital Communication, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.